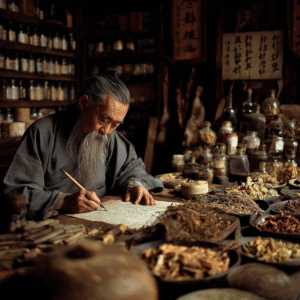

Herbs and Ancient Wisdom

Chinese traditional herbal medicine, a cornerstone of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), has been practiced for over 2,500 years, rooted in ancient philosophies and a profound understanding of nature. This system integrates herbs, acupuncture, diet, and lifestyle to restore balance and promote health. This blog explores the foundations of Chinese herbal medicine, key herbs used, and the enduring wisdom that continues to influence modern healthcare.

Foundations of Chinese Traditional Herbal Medicine

TCM is built on the principles of balance, particularly the concepts of Yin and Yang, and the flow of Qi (vital energy) through the body’s meridians. Illness is seen as an imbalance in these forces or disruptions in Qi, often influenced by external factors like climate or internal factors like emotions. Herbal medicine, one of TCM’s primary tools, uses plant-based remedies to harmonize the body, guided by texts like the Shennong Bencao Jing (The Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica), dating back to around 200 BCE.

Herbalists, often trained through apprenticeships or formal TCM schools, create formulas tailored to individual patients, combining multiple herbs to address specific imbalances. These formulas are typically administered as decoctions (teas), powders, pills, or topical applications. The holistic approach considers the patient’s physical, emotional, and environmental context, emphasizing prevention as much as treatment.

Key Herbs in Chinese Traditional Medicine

Chinese herbal medicine draws from a vast pharmacopeia of over 5,000 plants, minerals, and animal-derived substances, with herbs being the most prominent. Below are some key herbs and their traditional uses:

Ginseng (Ren Shen, Panax ginseng): Revered as a powerful tonic, ginseng is used to boost Qi, enhance energy, and support immunity. It is often prescribed for fatigue, stress, and recovery from illness.

Astragalus (Huang Qi, Astragalus membranaceus): Known for strengthening the immune system, astragalus root is used to prevent colds, improve digestion, and support lung function, often in soups or teas.

Licorice Root (Gan Cao, Glycyrrhiza uralensis): A harmonizing herb, licorice is added to many formulas to enhance their effects, soothe digestion, and reduce inflammation. It is also used for sore throats and coughs.

Goji Berries (Gou Qi Zi, Lycium barbarum): These nutrient-rich berries nourish the liver and kidneys, improve vision, and boost vitality. They are commonly consumed in teas, soups, or as snacks.

Dang Gui (Angelica sinensis): Often called “female ginseng,” dang gui is used to nourish blood, regulate menstruation, and alleviate pain. It is a key herb in women’s health formulas.

Ginger (Sheng Jiang, Zingiber officinale): A warming herb, ginger is used to aid digestion, relieve nausea, and dispel cold from the body, often brewed as a tea for colds or stomach upset.

Chrysanthemum (Ju Hua, Chrysanthemum morifolium): Used to clear heat and calm the liver, chrysanthemum tea treats headaches, eye strain, and fever, especially during hot weather.

Reishi Mushroom (Ling Zhi, Ganoderma lucidum): Valued for its calming and immune-boosting properties, reishi is used to promote longevity, reduce stress, and support respiratory health.

Herbs are rarely used alone; instead, they are combined in formulas based on principles like the “Four Natures” (hot, warm, cool, cold) and “Five Flavors” (sour, bitter, sweet, pungent, salty) to target specific conditions. Harvesting and preparation are precise, with roots often collected in autumn and flowers at peak bloom to maximize potency.

Spiritual and Philosophical Elements

Chinese herbal medicine is deeply tied to Taoist and Confucian philosophies, emphasizing harmony with nature. The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic), a foundational TCM text, outlines the interplay between humans and their environment, guiding herbal prescriptions. For example, “cooling” herbs like mint are used for “heat” conditions like fever, while “warming” herbs like cinnamon treat “cold” conditions like poor circulation.

Spiritual practices, such as meditation or Qigong, often complement herbal treatments, reinforcing the connection between mind and body. Healers may also consider seasonal changes or the patient’s emotional state, as emotions like anger or grief are believed to affect specific organs (e.g., anger impacts the liver).

Historical and Modern Influence

Chinese herbal medicine has evolved over centuries, with significant advancements during the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) dynasties. The Bencao Gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica) by Li Shizhen in the 16th century cataloged over 1,800 substances, showcasing the depth of this knowledge. Trade along the Silk Road introduced new herbs and influences from Persia, India, and beyond, enriching the pharmacopeia.

Today, TCM is practiced worldwide, with herbs like ginseng and goji berries gaining global popularity. Modern research validates many traditional uses, such as astragalus for immune support or ginger for nausea. In China, TCM is integrated into hospitals alongside Western medicine, with herbal formulas used for conditions like respiratory diseases and chronic pain. However, challenges like overharvesting of herbs and standardization of formulas persist.

Conclusion

Chinese traditional herbal medicine is a testament to the enduring wisdom of ancient healers who saw health as a balance between body, mind, and nature. Its vast array of herbs, from ginseng to reishi, continues to offer effective remedies, supported by both tradition and modern science. As interest in holistic health grows, TCM remains a vital link to ancient knowledge, inspiring new generations to embrace its time-tested practices.

For further reading, explore The Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica for historical insights or Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica by Dan Bensky for a comprehensive modern guide.